Aliveness as a Training Methodology

How many key principles of nonlinear pedagogy and the constraints-led approach are enveloped by the aliveness philosophy in martial arts.

In meditating on Matt Thornton’s 2017 essay, Why Aliveness?, I was smitten with just how much this philosophy is able to encapsulate under one label.

He writes,

Aliveness is about the freedom to use whatever works in the moment. It's the right action at right time.

The first mentions of aliveness in Bruce Lee’s work speak of authenticity and spontaneity in one’s movement.

Matt Thornton further developed the concept into timing, energy, and motion, extending a few notes from Lee into a rich philosophy of training.

In boiling down the most important dynamic elements of combat sports, I tried to further refine aliveness into unscripted and uncooperative interaction. I believe this definition is immediately clear about the freeness of action and genuineness of antagonism across combat sports.

My definition is also formulated in such a way that aliveness doesn’t necessarily have to entail maximum intensity in every practice activity; it’s scalable to different training needs and skill levels.

As Thornton writes concerning the scalability of aliveness,

[…] Similar to when I hear some Instructors say “Aliveness is just sparring” – I know they still don’t get it.

…

It’s not about the speed of the movement. It’s about the Alive opponent. Bullshit sped up, is still bullshit.

Anyone whose [sic] ever had a slow roll in BJJ, knows that training Alive, and training hard and or fast, are not necessarily synonymous. Again, it’s timing, energy, and motion.

The unscripted/uncooperative definition also captures Lee’s conception of aliveness, since both the self-determined nature of unscripted movements under the pressure of an antagonist must eventually lead to a totally unique, i.e. authentic quality of movement solutions.

In this way, I don’t think my work to extend aliveness has lost anything from Lee or Thornton. It doesn’t fundamentally change or rebuff their ideas.

Rather, my work continues to build upon their shoulders, they being giants in the philosophy of martial arts training.

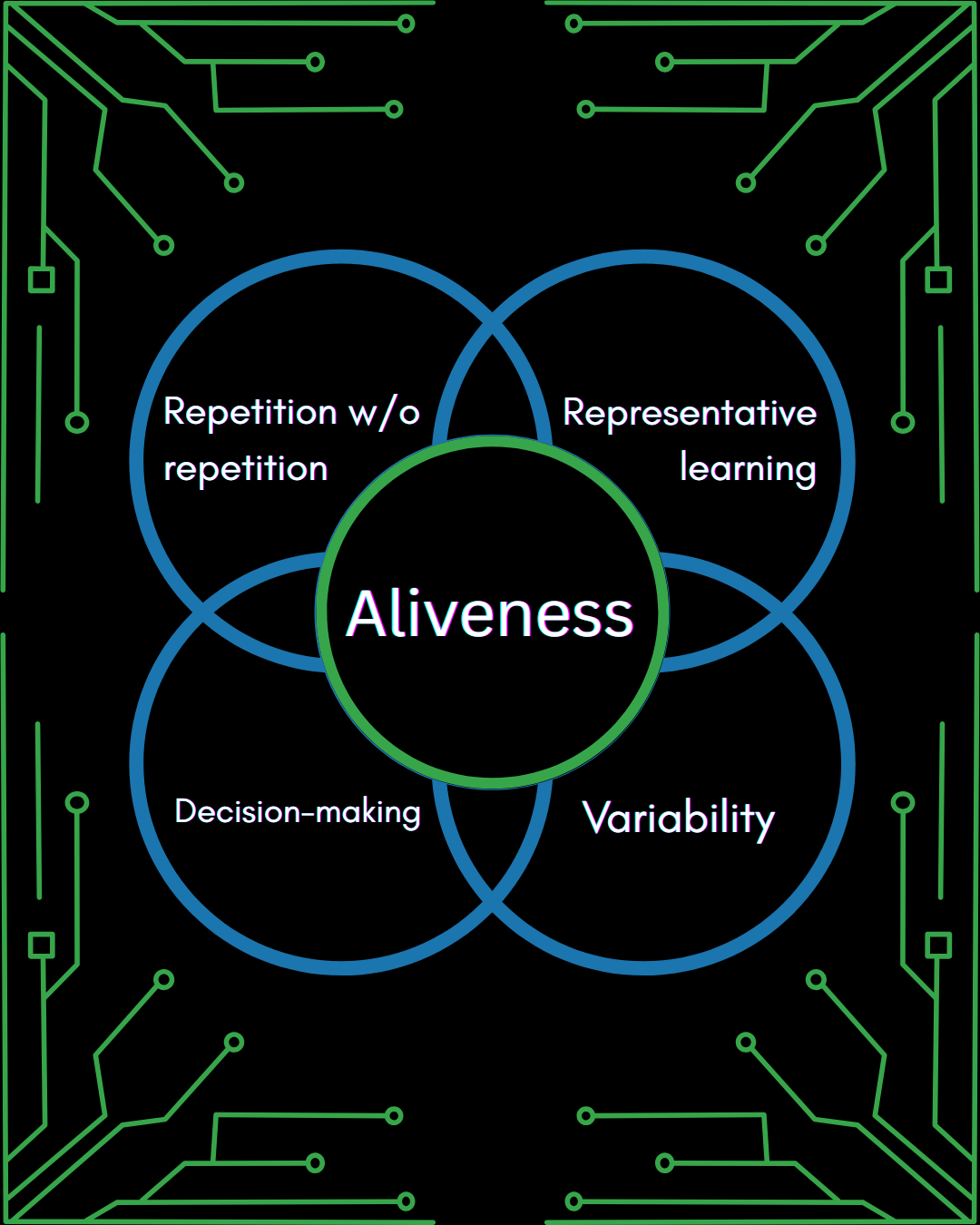

But wrapped up in these notions are implicitly necessary overlap with the key ecological principles of the constraints-led approach, such as representative learning design, repetition without repetition, decision-making, and variability.

With this in mind, let’s explore how the major elements of the ecological approach are implied by alive training—

Even, as you will see, how it has become a methodology unto itself.

Representative learning design in Aliveness

Representative learning design (RLD) is about using the most important dynamics of a given sport to make practice more likely to transfer to the competition or performance environment.

A more technical way of defining RLD is that it’s a practice design principle for creating training tasks that mirror the key constraints, information sources, and decision-making demands of actual competition.

All combat sports—and even self-defense—are fundamentally alive in the unscripted and uncooperative sense. It’s for this reason that I have said that aliveness is the floor for representative learning design in combat sports. It’s table stakes.

Now, that doesn’t mean that because an exercise is alive it is perfectly representative. It doesn’t. It just means it’s the first and primary standard of representativeness.

Thus, RLD is encapsulated by aliveness insofar as it is implied by it.

There are more considerations for good representative design, but if you’re training your sport with aliveness, that training will always be some level of representative.

Decision-making in Aliveness

Because players must determine their own movements within the constraints of a truly alive exercise, genuine decision-making is always preserved.

Aliveness demands timing from the energy and motion of its participating athletes. Less appreciated are the necessary decisions that lead to the emergence of all these observable elements.

When you execute a one step routine, everything is scripted from start to finish. Even the timing of when to execute the first movement is relatively fixed. There is no point during a one step where a decision must be made, and thus no adaptations are demanded of the two participants.

When an exercise is alive, however, decisions both conscious and unconscious are demanded of the athlete at every moment.

Where this is no script to follow, and opponents are not cooperating with one another, learners must commit to actions based on emergent, often confusing information. And they must adapt moment-to-moment if those decisions fail to yield their intended goals.

This leads me to an important point with regard to the importance of an ecological approach:

Combat sports decision-making is specialized decision-making. Windows of opportunity open and close as quickly as a punch can be thrown, a head can move.

Big life decisions often give you a runway of days, weeks, and months, but big fight decisions are demanded of you in seconds, a second, less than a second.

You cannot train to make good decisions in a fight with exercises that never ask you to make decisions as quickly or as rapidly as a fight requires.

Repetition without repetition in Aliveness

If a solution to a given practice task is not prescribed, then the player is free to fulfill the task however he can manage.

And without that prescription, each attempt at the task also presents opportunities to fulfill it in different ways—especially as that task is engaged in with different opponents who present unique challenges.

This is the exact spirit behind Bernstein’s repetition without repetition, the motor learning principle that skill acquisition comes from solving the same movement problem in different ways, rather than repeating an identical motion.

In other words, we want to allow (and encourage) learners to solve the same basic problem in different ways.

Aliveness is such that almost every trial you make to fulfill a task will force you to find different ways to solve it. In the context of martial arts, you will also be forced to engage in the same task with different opponents, which adds another layer of repetition without repetition and a need for deep skill adaptability.

Variability in Aliveness

Variable task design involves deliberately manipulating key parameters of a skill during training to improve long-term retention and transfer to new situations. In other sports, these parameters often force, distance, speed, or environmental context.

Unlike constant practice, where learners repeat the same movement, variable practice encourages learners to search for new movement solutions and adapt to changing conditions, making it particularly effective for open skills like combat sports.

Aliveness is unique in that the need to manipulate specific parameters in a practice task dissipate into its raw intrinsic levels of variability. You can attempt the same task 100 times and have 100 qualitatively different experiences.

These variable conditions create adaptable athletes who can better perceive the environmental information they need for skillful action.

But as ecological research continues to show, this movement noise we call variability tends to create safer training environments in addition to superior adaptability in athletes. Variable practice task designs have been shown to lead to fewer injuries, despite how chaotic they look to observers.

Variability in practice tasks allows the body to coordinate how it wants to, condition itself through a manifold of movements and conditions, and through all this dodge overuse and create joints that are more resilient to a variety of unexpected positions.

Live practice tasks are always variable, because they do not follow a script. The same task unfolds differently every time you attempt to complete it.

And if you’re doing the constraints-led approach right, the types of practice tasks will be variable, too, not just the quality of the tasks themselves. This pulls in other learning effects, like interleaving and contextual interference.

!["Errors" are Necessary for Perception and Skill [How We Learn to Move, Chapter 2 Companion]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!O2Hx!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff825d1f2-bc10-4f64-a141-53e21f57b9e1_1456x1048.png)